In Defense of Conflict and Inefficiency

Few people are happy with the US government these days. Recent Gallup polls show that 71% of people are somewhat or very dissatisfied by "our system of government and how well it works". Common complaints are that government's too polarized and full of conflict, or that it's bureaucratic and inefficient and can't get things done.

These are both fair assessments. Our government is full of conflict and inefficient. But it's worth asking: are conflict and inefficiency inherently bad things?

On Conflict

Daniel Walters recently summarized the work of Chantal Mouffe, who celebrated the role of conflict in democracy. "For Mouffe, disagreement is not just an empirical fact—it is constitutive of the very idea of democracy itself," he writes. Societies are constantly faced with meaningful decisions about which people can reasonably disagree. Our needs are in conflict, and it is through democratic conflict that we determine whose needs win out for now.

adrienne maree brown echoes this point: "Conflict, and growing community that can hold political difference, are actually healthy, generative, necessary moves for vibrant visions to be actualized."

Whether you're talking about the societal, community, or interpersonal level, conflict can be healthy and productive. But if that's so, why is polarization making us so miserable?

One answer is that it matters what you're having conflict over. It's less stressful to disagree about transit policy than about who has a right to vote, or marry, or walk down the streets safely.

Another, more counter-intuitive answer, is that polarization is not a sign of conflict but a sign of suppressed conflict.

Mouffe notes that in highly unequal societies, the powerful are able to avoid engagement with those they've marginalized. Denied access to democratic arenas in which to fight the powerful, people resort to more polarized forms of conflict like protests, riots, or even revolution. Similarly, at the interpersonal level, public call outs and cancellations often occur when there are no other means to hold people and institutions accountable.

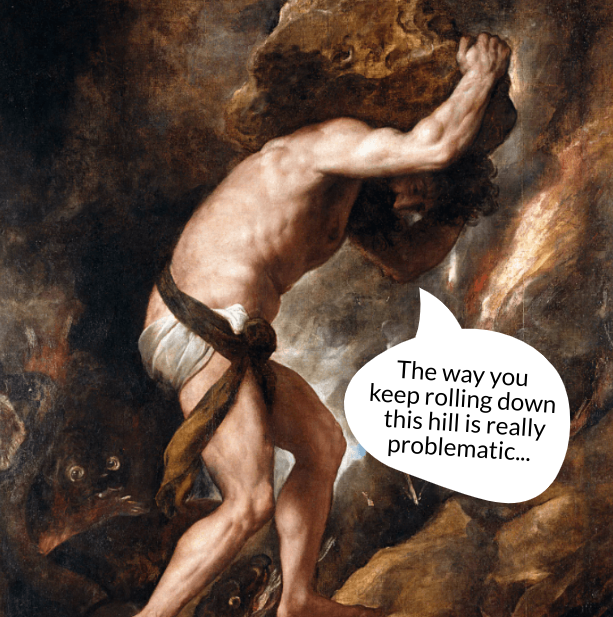

But this isn't the only circumstance in which people use call outs. brown notes that they're often used instead of a more direct, person-to-person approach to people who are potentially reachable. Call outs can be their own way of avoiding conflict. And when they're used as a form of conflict avoidance, they often increase polarization. They're consumed rather than resolved. They cycle endlessly, like Sisyphus rolling his boulder up the hill—if he was arguing with the boulder the whole time.

The systems around us discourage good conflict, and encourage bad conflict/polarization. As someone whose always lived in solidly blue states, there's no incentive for me to engage in political debate with my neighbors, even though statistically, at least a few of them must be Republicans. Instead, I've traveled to other states to canvass strangers, often unsuccessfully. Or I go online and try to engage with tweet after Sisyphean tweet.

To fix the polarization problem, we can't avoid conflict. We have to change the kind of conflicts we have. Walters writes (emphasis mine):

"Across the board, from constitutional law to criminal law to administrative law, the problem we face is the lack of opportunity for genuine contestation over the structural premises that have led to the accumulation of power and the exclusion of the perspectives of marginalized people. While our instincts are often to avoid or be indirect about political conflicts, this tendency must be unlearned if we are to reclaim an equal share in determining our collective political identity. Friendly contestation is the glue that holds a pluralistic democracy together in the long run."

On Inefficiency

As with conflict, there can be both good and bad kinds of inefficiency.

There's a cult of efficiency in the United States that assumes all efficiency is good and all inefficiency is bad. But the last several years have clearly put the lie to these assumptions.

Our global social networks, with long distance travel and the easy ability to make connections to strangers, have very efficiently spread Covid-19 in all its variants. Online, viral misinformation spreads efficiently across networks, reaching millions before being reported and hopefully taken down. In a network, efficiency can make you more vulnerable to viruses both physical and informational—and inefficiency can make you more resilient.

Often efficiency is neither all good nor all bad, but something in between. For instance, social media technology allows us to build up movements more quickly. But that efficiency can leave the movements hollow, deprived of the social connections that inefficiency fertilizes.

In Red State Revolt, Eric Blanc documents the 2019 teachers strikes. Strikes in Oklahoma were organized primarily through Facebook, instead of through a combination of online messaging, in-person activism, and union engagement as they were in Arizona and West Virginia.

"The ease of mobilization and communication provided by Facebook has real downsides. In the internet age, mass protests can scale up very quickly - sometimes too quickly for powerful organizations to develop in the process. Without the political and infrastructure forged through in-person organizing, protest movements that rely on social media can be structurally fragile [...] Oklahoma's grassroots leaders, for example, focused most of their energy on Facebook, underestimating the urgency of building up to a strike through escalating workplace actions and collective organization. In contrast, [West Virginia teachers] Comer and O'Neal were school-site organizers who intentionally focused on getting educators to participate in protests, workplace actions, and organizer meetings."

The West Virginia and Arizona strikers largely won their demands. The Oklahoma strikers did not.

Zeynep Tufecki describes a similar issue with the Arab Spring protests:

"If you wanted to organize, let’s say, the Montgomery bus boycott in the 1950s and ’60s, during that time, or the March on Washington, you had to spend a lot of time. The March on Washington took, I think, six months just to do the logistics. You don’t have Excel spreadsheets and things like that. From an idea to a march was about 10 years. [...] Whereas right now, with social media, [...] if you’re a movement, that kind of speedy exponential growth, without having built other parts of the infrastructure, means that when the government does come for you, you don’t have even a decision-making system. You don’t even know, “How do I respond to it?"

Social media helps people connect and plan quickly. But time is essential to relationship-building. In a movement, good inefficiency builds relationships.

What about in government? You may remember Donald Trump's complaints about the "deep state": the great numbers of civil servants who disagreed with his policies and resisted implementing his orders. They were being purposefully, protectively inefficient, and they were legally allowed to do so, within reason.

The United States didn't always have a protected civil service. Through the early 19th century, we operated under a spoils system. Any civil servant could be fired by the President at any time, and there was usually significant turnover whenever the Presidency changed hands, especially between political parties. The Pendleton Civil Service Reform Act of 1883 established the protected civil service, and this was done in part to decrease partisanship.

Trump attempted to subvert the Pendleton Act by creating Schedule F, a new class of federal employees that could be fired at will. But he waited too long to do so. The executive order was signed in October 2020 and there was not enough time to reclassify everyone before Trump left office. (Biden revoked the executive order immediately.)

Good inefficiency protects against abuse of power. It can also, as mentioned above, help build institutions and relationships.

Just like conflict, inefficiency isn't always good—far from it. But it can be good.

On Technology

So how can we promote good conflict and good inefficiency?

The answer is not through technology—at least not technology like we've been building. Software engineers and entrepreneurs tend to be among the most passionate converts to the cult of efficiency, and they tend to eschew conflict with the confidence of those for whom the status quo works just fine.

A good example of technology suppressing conflict in the name of efficiency comes from Rebecca Crootof:

"Once upon a time, missing a payment on your leased car would be the first of a multi-step negotiation between you and a car dealership, bounded by contract law and consumer protection rules, mediated and ultimately enforced by the government. You might have to pay a late fee, or negotiate a loan deferment, but usually a company would not repossess your car until after two or even three consecutive skipped payments. Today, however, car companies are using starter interrupt devices to remotely “boot” cars just days after a payment is missed. This digital repossession creates an obvious risk of injury when an otherwise operational car doesn’t start: as noted in a New York Times article, there have been reports of parents unable to take children to the emergency room, individuals marooned in dangerous neighborhoods, and cars that were disabled while idling in intersections."

A person who has missed their car payments has done so because they have conflicting needs—needs which may be more important, to themselves and to society, than making car payments. And the laws and consumer protection rules which make repossession a slow process are inefficient for very good reason.

But the companies who build and buy these "smart" technologies don't care about any of that. They want to end the conflict as efficiently as possibly—with themselves on top, of course.

Our current technologies, created as they are by the powerful for the powerful, tend to minimize conflict and inefficiency. But we don't have to continue in this way. We can reform our technologies, and our society as a whole.

In order to do so, we need to have a more nuanced approach to conflict and inefficiency. And that starts with recognizing all the good things they can bring.

Member discussion